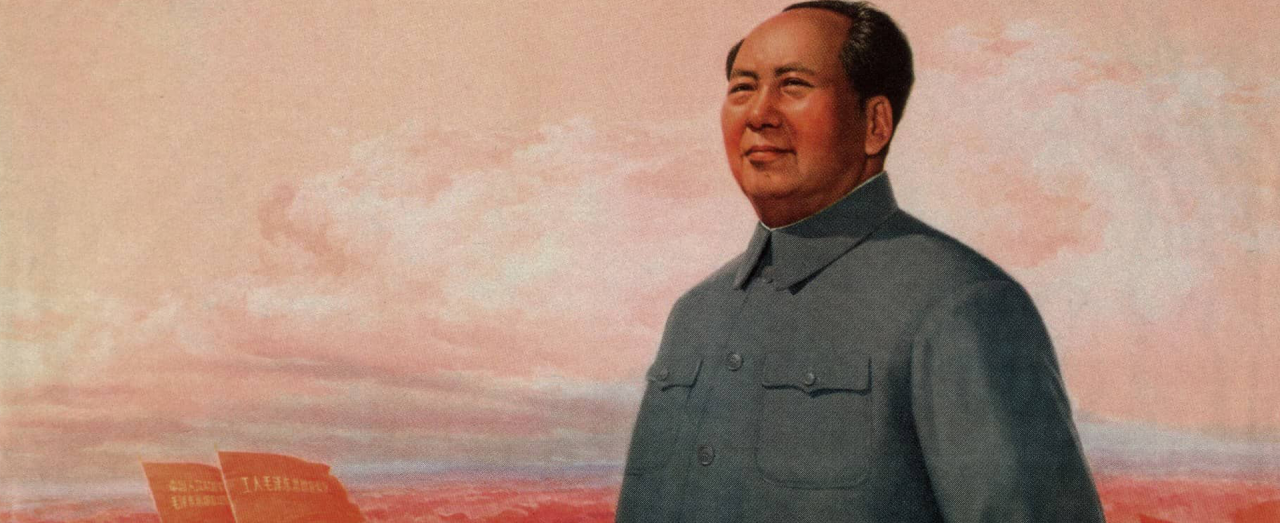

Maoism has been around, at least in name, since the mid-1940s. Numerous attempts were made to elevate Mao Zedong Thought to the level of an “-ism,” much to Mao’s displeasure. In 1948, in a correspondence with Wu Yuzhang, then president of North China University, he refused to allow his name to be listed alongside Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin, writing, “there is no Maoism”. In 1955, at a conference, again it was suggested that Mao Zedong Thought be elevated to Maoism. Mao replied simply, “Marxism-Leninism is the trunk of the tree; I am just a twig.” This was not mere modesty, this was dialectical.

What’s in a name?

To uphold Maoism is to hold the theory and practice of Mao Zedong as a new, higher stage of development in socialist science. Historian Hu Angang described this Maoist tendency as a precursor to the cult of personality which would emerge around Mao in the events of and leading up to the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. In the decades following Mao’s death, however, Maoism was given the proper scientific treatment and thoroughly systematized. The exemplar of this and the ideological predecessor to most Maoist parties today was the Revolutionary Internationalist Movement [RIM]. The publishing of their declaration, Long Live Marxism-Leninism-Maoism!, is considered by many to be the moment when Maoism was crystallized as a theory, taking in the experience not just of the Communist Party of China, but other parties such as the Communist Party of Peru, the first to lead a revolution using Marxist-Leninist-Maoist theory.

In order to examine Maoism as an -ism, we must first understand the theoretical and practical “ruptures” that supposedly make Maoism a higher stage. I will now quote Long Live Marxism-Leninism-Maoism! at length.

Mao Zedong developed Marxism-Leninism to a new and higher stage in the course of his many decades of leading the Chinese Revolution, the world-wide struggle against modern revisionism, and, most importantly, in finding in theory and practice the method of continuing the revolution under the dictatorship of the proletariat to prevent the restoration of capitalism and continue the advance toward communism.

Mao Zedong comprehensively developed the military science of the proletariat through his theory and practice of People’s War.

Mao solved the problem of how to make revolution in a country dominated by imperialism. … This means protracted People’s War.

Mao Zedong greatly developed the proletarian philosophy, dialectical materialism. In particular, he stressed that the law of contradiction, the unity and struggle of opposites, is the fundamental law governing nature and society. He pointed out that the unity and identity of all things is temporary and relative, while the struggle between opposites is ceaseless and absolute, and this gives rise to radical ruptures and revolutionary leaps. He masterfully applied this understanding to the analysis of the relationship between theory and practice, stressing that practice is both the sole source and ultimate criterion of the truth and emphasizing the leap from theory to revolutionary practice.

Mao Zedong further developed the understanding that the “people and the people alone are the motive force in the making of world history.” He developed the understanding of the mass line.

Mao taught that the Party must play the vanguard role – before, during, and after the seizure of power … He developed the understanding of how to preserve the proletarian revolutionary character of the Party through waging an active ideological struggle against bourgeois and petit bourgeois influences in its ranks.

In short, according to the RIM, Maoism teaches that: 1) socialism is class society and so class struggle and the revolution continue under the dictatorship of the proletariat; 2) People’s War is a universally applicable strategy and necessary for the success of the revolution; 3) the party must follow the mass line method of leadership and become a mass party; 4) the struggle against revisionism will take place within the party. Setting aside for now the question of the correctness or incorrectness of these theories, it must first be asked: why did Mao insist that “there is no Maoism,” that Mao Zedong Thought was “just a twig” on the tree of Marxism-Leninism? Because nothing truly new is created in Mao Zedong Thought, there is no rupture.

Refinement

The theories themselves were not yet elaborated when Mao began formulating them, of course, but the foundation was already inherent in Marxism-Leninism. Mao’s theories arose not as a result of any new developments in the objective conditions of the world and their subsequent analysis, but rather from the application of Marxism-Leninism to the objective conditions of semi-feudalism in general and Chinese semi-feudalism, semi-colonialism in particular.

Mao’s theories are also anti-revisionist, criticizing both the revisionist strains within the Communist Party of China and, later, the Khrushchevite revisionism of the Soviet Union. He writes:

It does happen that the original ideas, theories, plans, or programmes fail to correspond with reality either in whole or in part and are wholly or partially incorrect. In many instances, failures must be repeated many times before errors can be corrected and correspondence with the laws of the objective process achieved … when that point is reached, the movement of human knowledge regarding a certain objective process at a certain stage of its development may be considered completed.

It often happens, however, that thinking lags behind reality; this is because man’s cognition is limited by numerous social conditions. We are opposed to die-hards in the revolutionary ranks whose thinking fails to advance with changing objective circumstance and has manifested itself historically as Right opportunism.

We are also opposed to “Left” phrase-mongering. The thinking of “Leftists” outstrips a given stage of development of the objective process; some regard their fantasies as truth, while others strain to realize in the present what can only be realized in the future.

In Mao Zedong Thought we find not new developments but new refinements and applications of existing theories. His elaboration on the dialectical materialist conception of knowledge is not new in anyway. He is pulling entirely from Marx, Engels, and Lenin before him. Though the RIM credits Mao with these theories, it is Mao himself who points out in On Contradiction that Lenin was the one who long ago defined dialectics as “the study of contradiction in the very essence of objects,” and referred to the law of the unity of opposites as the “kernel” of dialectics. Moreover, we can find everything from the Two World Outlooks to the law of the transformation of quantity into quality just in Engels’ Dialectics of Nature.

Any serious study of Marxism could’ve concluded the same things. No new developments gave rise to Mao’s contributions. He is more than anything taking Stalin’s advice and reiterating the “so-called “generally-known” truths” of Marxism, so as to “educate [these comrades] in Marxism-Leninism.” Thus, Mao’s theories are rightfully considered an anti-revisionist thought, not an -ism.

Quality and Quantity

Mao examines the dialectical materialist conception of knowledge in On Practice, explaining that all rational knowledge and correct thinking is resultant first on direct experience and perception, then on cognition. “Rational knowledge depends upon perceptual knowledge and perceptual knowledge remains to be developed into rational knowledge.” Before any concept can be synthesized, there must be the perceptually knowledge of the objective world. And once there are conceptions, they must be tested, for “It is only when the data of perception are very rich (not fragmentary) and correspond to reality (are not illusory) that they can be the basis for forming correct concepts and theories.” In doing so, he elucidates also the law of the transformation of quantity into quality and vice versa, wherein a quantitative change leads to a qualitative change.

He touches upon the proof of this law in the historical development of Marxism in On Contradiction, noting that “As the social economy of many European countries advanced to the stage of highly developed capitalism, as the forces of production, the class struggle, and the science developed to a level unprecedented in history, and as the industrial proletariat became the greatest motive force in historical development, there arose the Marxist world outlook of materialist dialectics.” He expands on this further in On Practice:

Marxism could be the product only of capitalist society. Marx, in the era of laissez-faire capitalism, could not concretely know certain laws peculiar to the era of imperialism … because imperialism had not yet emerged. … only Lenin and Stalin could understand this task. … the reason why Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Stalin could work out their theories was mainly that they personally took part in the practice of the class struggle and the scientific experimentation of their time.

By “their time,” what is meant is the objective conditions of the world at the time they were studying. Both Marx and Engels and Lenin and Stalin made legitimate theoretical ruptures because they had begun analyzing an entirely new period.

In Marx and Engels’ time, a scientific, dialectical materialist conception did not yet exist, nor had a dialectical materialist analysis of capitalism been undertaken. The closest to these at the time was Hegel’s idealism and the bourgeois mechanical materialism of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. By the mid-nineteenth century, however, with the industrial revolution having come to a close, great industrial factories and mills had been erected employing armies of proletarians. Small artisanal producers had finally been banished and so went with them many of the last ideological and economic vestiges of feudalism in Western and Central Europe. New objective conditions arose which the ideology of the previous centuries was unable to comprehend and which necessitated a new theoretical rupture. “No genius could have succeeded,” Mao writes, “lacking this condition.” Their theoretical rupture, the crystallization of dialectical and historical materialism, was only made possible due to the fact that Marx and Engels were studying capitalism in the era of capitalism, science in the scientific age.

But Marx and Engels, in their time, studied a different kind of capitalism than Lenin and Stalin practiced in. In Lenin and Stalin’s time, imperialism had emerged and capitalism was qualitatively transformed; thus, a new theoretical rupture in continuity with the Marxism of Marx and Engels was needed to make dialectical materialism correspond again with the objective laws of the new stage. We must note that imperialism emerged in accordance to the law of the transformation of quantity into quality. Capitalism underwent a quantitative change with the increase in the concentration of production which resulted in the rise of finance capital, a qualitative change. (Hence why the first thirty or so pages of Imperialism are just statistics, i.e. quantities.) And so it is accurate to declare that Leninism emerged in and from the era of imperialism and that it is a rupture in continuity with Marxism because it brought Marxism back into accordance with the objective laws of the new imperialist stage of capitalism.

The Maoist J. Moufawad-Paul, however, rails against this in his Continuity and Rupture, calling Mao’s conclusion “pseudo-science” (though he does not credit Mao for this conclusion and instead gives credit to the New Communist Movement). He writes:

The fact that old “Maoism” could not think beyond its Marxist-Leninist limits was demonstrated in the clichéd formula that Leninism was “the Marxism of the imperialist era”. Such a formula … was ultimately unscientific.

The first problem with this formulation is that it is an impoverishment of Leninism. … Leninism thus becomes a phenomenon that is important because of a time … not because of the theorizations it has produced regarding this time. The formulation … explains nothing of itself by a reduction to the unscientific notion of a zeitgeist.

The second problem … is that it fails to recognize that imperialism existed prior to Lenin and that the Marxism of Marx and Engels was also a “Marxism of the imperialist era” but, clearly, a different era of imperialism.

In this sense, Maoism could be called the communism of the socialist era.

It seems Moufawad-Paul has completely forgotten the law of the transformation of quantity into quality. If not, then he has knowingly destroyed his argument in the very sentence with which he makes it.

He notes that imperialism did exist beforehand but admits that it existed in another form. “Of course,” he writes, “Lenin’s discussion of imperialism is an examination of an imperialism transformed by capitalism,” i.e. imperialism which had undergone a qualitative transformation since Marx and Engels’ time. By acknowledging this and yet still denying the start of an imperialist era distinct from the time of Marx and Engels, he has thrown the law of the transformation of quantity into quality to the wind.

We see this again when he declares that: “socialist revolutions alter the meaning of global imperialism.” Indeed this is true, but, to date, socialist revolutions have only ever altered imperialism quantitatively. A few liberated nations or independent blocs have not changed in any qualitative way the nature or function of capitalist imperialism. It is clear that we are very much still in the same era as Lenin and so there have not yet been grounds for a new theoretical rupture. All analyses since Lenin and Stalin up to this point have only ever operated within the framework of Leninism and within the objective conditions of imperialism.

Moreover, Moufawad-Paul, despite denying actually existing socialism (and thus bringing to a swift end the era of socialism), says that Maoism can be considered in a sense a product of “the socialist era.” When, I must ask, was this socialist era? If it emerged with the first socialist state then did not Lenin and Stalin practice under the socialist era as well? Are not their theoretical and practical developments operating in the era of socialism? If that is the case, then The Foundations of Leninism it can be said serves to crystallize Marxism-Leninism both as the Marxism of the imperialist era and the socialist era. And it must be according the dialectic of continuity and rupture.

Again, it must also be noted that Mao made no theoretical ruptures in the Marxist understanding of socialism, since Lenin and Stalin had long since understood socialism as class society. For example, in State and Revolution, Lenin states: “The proletariat needs state power both for the purpose of crushing the resistance of the exploiters and for the purpose of guiding the great mass of the population-the peasantry, the petty-bourgeoisie, the semi-proletarians-in the work of organizing a socialist economy. By educating a workers’ party, Marxism educates the vanguard of the proletariat, … capable of leading the whole people [Lenin’s italics] to socialism, of directing and organizing the new order.” Thus we see his conception of Maoism as a theoretical rupture crumble before the vast theorizations of Lenin and Stalin, especially during their time leading the October Revolution down the path of socialist development.

Lenin’s understanding of the state again highlights the failure of Maoists to retain and understand the law of the transformation of quantity into quality. For, as the state changes qualitatively from a bourgeois dictatorship to a proletarian dictatorship, the foundation of all bourgeois ideology is gradually pulled out from under it, first with one great tug (revolution) and then gradually with the eventual disappearance of capitalist production altogether and its replacement by socialist production. By understanding this, as well as, as Stalin puts it, that “the history of the development of society is above all the history of the development of production,” we come to realize that continuing the revolution during the dictatorship of the proletariat is entirely unnecessary.

Did the bourgeoisie continue the revolution against feudalism after they’d already emerged victorious? No. Feudalism suffered its great defeat at the hands of the young capitalists and was eventually relegated to history by the inevitable development of capitalism. The presence of feudal classes under capitalism forms a contradiction but it is not an antagonistic contradiction. “Difference itself is contradiction.” says Mao. “The question is of different kinds of contradiction, not of the presence or absence of contradiction. … unlike the contradiction between labor and capital, it will not become intensified into antagonism or assume the form of class struggle.”

As socialist development goes forward, the small quantity of bourgeois producers will be reduced, just as the feudal lords were, to impotency and finally death, taking whatever’s left of the bourgeois ideological superstructure with them. By the diminution of their numbers and economic output, they will have been qualitatively transformed into a class without intense, antagonistic opposition to the proletariat. The same applies even more so to the peasantry and the semi-proletarians.

Maoists like Moufawad-Paul insist, against Stalin’s warnings, that the party of the proletariat must be a mass party in order to eliminate prejudice. What they do not grasp is that, as prejudice is a product of capitalism, it too will be gradually destroyed simply because it is incompatible with the new socialist system. Moufawad-Paul is correct to say, “Class is always clothed in the garments of oppression” and that “there is never an instance of purely abstract class struggle that is stripped from its ideological trappings,” but he is wrong to say that since “Capitalism has never been a pure mode of production” (Louis Althusser’s revisionist assertion) the “final instance” of capitalism’s lingering effects on the ideological superstructure “never arrives,” that bourgeois ideology will not or cannot eventually wither away.

Moufawad-Paul uses capitalism’s few remnants of feudal ideology to demonstrate the lasting effects of class hegemony on ideology but fails, again, to see the qualitative transformations which have taken place. The remaining ideological trappings of feudalism have survived only because they’ve served the interests of the now ascendant bourgeoisie. Even then, it has long been noted that all tradition and ideology has fallen before the hunt for profit.

It must be asked, what is the usefulness of prejudice, of racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, etc., to the proletariat? The proletariat does not have its very class survival vested in the exploitation of another class and thus has no need for ideological justifications for oppression and exploitation. What reactionary attitudes we will surely see survive the revolution will just as surely die off as the economic base for such reactionary thinking disintegrates. To deny this is to deny the very possibility of communism.

All the Wrong Lessons

The last thing which must be addressed is Maoism’s claims of universality and necessity. It is clear that the mass line method of leadership and People’s War are very useful. But the simple fact that revolutions have succeeded in the same objection conditions as the Chinese Revolution (the age of imperialism and socialism) without employing these methods and strategies proves that they are not prerequisites for revolution.

This makes Maoism distinct from similar strains of thought. Mao Zedong Thought, the ideological parent of Maoism, is not in of itself all that unique. Strains like Fidelismo and Ho Chi Minh Thought exist and have proven just as successful as Mao’s theories have, if not moreso. Why then are there no “Ho-ists”? Where are the great international movements upholding “Castroism” as the third stage of Marxist science? What makes the Maoist phenomenon different? The difference is that Chinese ultra-leftism arose in opposition to Soviet opportunism and grafted itself onto the world communist movement due to the significance of the Sino-Soviet split (much in the same way Trotskyism forever left its mark not due to its success in practice but to Trotsky’s expulsion from the Party and the rise and fall of the Fourth International).

Like Trotskyists, Maoists have learned all the wrong lessons from the historical experience of Mao Zedong Thought. They have been blinded by Mao’s criticism of the Soviet Union and so they dogmatically cling to an outdated post-split mindset. Mao was correct to oppose Khrushchevite revisionism, but his Three Worlds theory was incorrect and he was horribly wrong to support CIA stooges, butchers, and anti-communists across the world for no other reason than to oppose the Soviet Union. The modern belief in the “degeneration” of all actually existing socialist states, Soviet “social imperialism,” and, for some, the descent into defeatist third-worldism all bare the scar of a post-split defensiveness.

This sectarian and ultra-leftist tendency manifested itself clearly in the cult of personality which formed around Mao and survives today in the belief in Chinese “imperialism” and “capitalist restoration.” This is illustrated even further in the sectarianism and wrecker activity of so many Western Red Guard organizations. But by far the worst of Maoism was demonstrated in the extreme dogmatism and cultishness of the Communist Party of Peru who lit their Shining Path with the flames of the Cuban, Soviet, and Chinese embassies they destroyed in pointless terror attacks.

The sad part is that Mao saw it coming. He fought against every attempt to elevate Mao Zedong Thought to Maoism or to his literal thoughts. He prohibited the naming of streets and buildings in his honor, rejected idolization, and encouraged criticism of himself and his policies at all levels of Party and governmental work.

“Men are not sages,” he said. “Even saints make mistakes.” As with all things, we must look critically at Mao’s successes and failures just as he encouraged for most of his life. We must reject what is wrong and chase what is right. We must be objective. We must reject all dogmatism and cultishness. We must reject Maoism as Mao himself did.

Leave a Reply